The things I do for compost.... (on soil ecology and spring garden prep!)

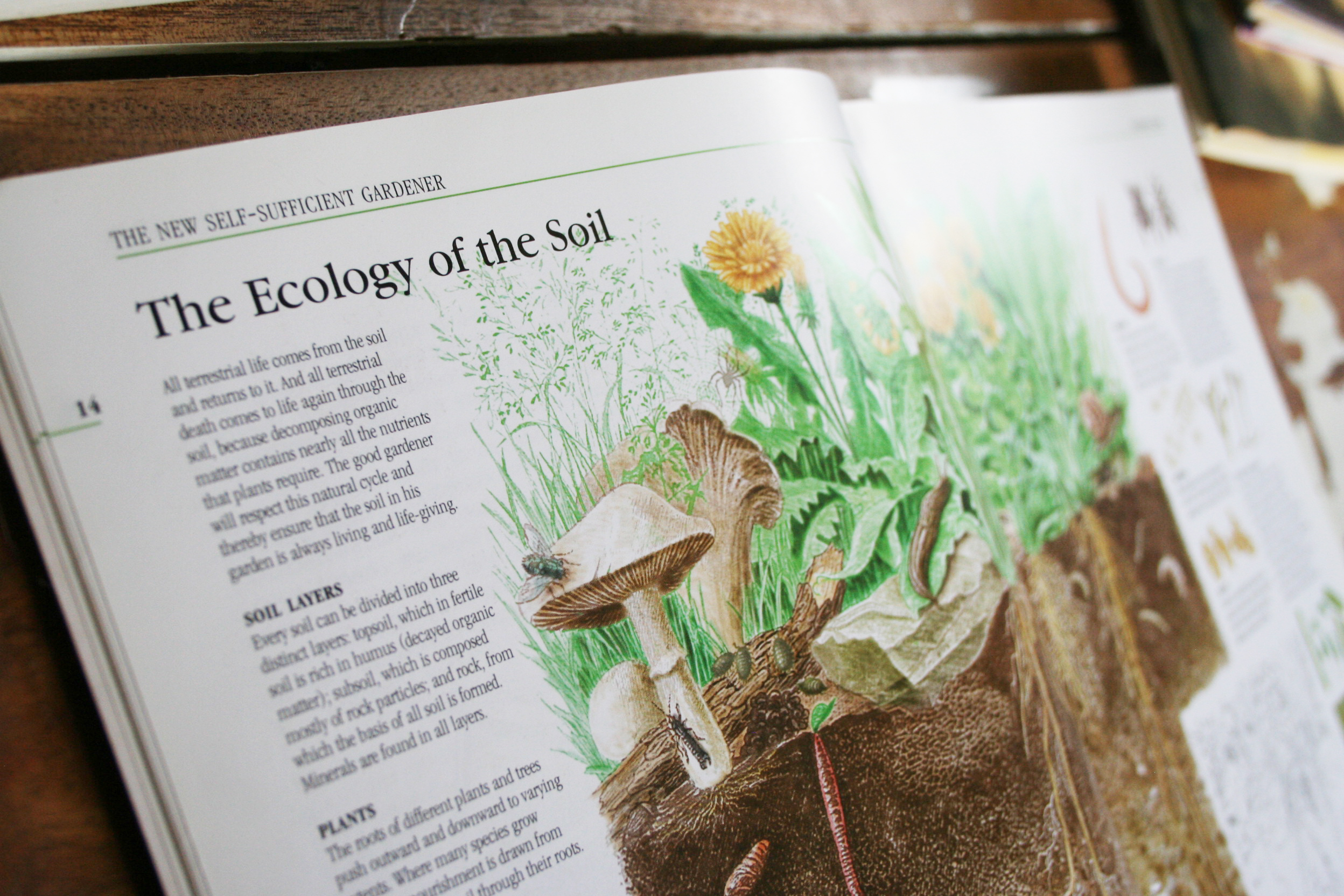

Three years ago, when I decided we needed to try and grow as much food as possible on our 1/5 acre lot, I bought a book. I declared I would read it from cover to cover. I learned that in order to have a thriving garden - you MUST start with the soil. Since then, I've become a bit obsessed with dirt, compost, manure and humus. Let me explain...

Many things that I read about that first year would only prove helpful as I got out in the garden and dug. When we first dug up most of the lawn in 2011, we removed the sod layer with a sod cutter, then rototilled. The moist soil underneath seemed dark - which was good, we thought. We left it in mounds as we decided where to put our beds. After a day or two, the soil began to dry out and it's real qualities were evident. There was little to no texture, besides thick, hard, dense CLAY. What looked dark and crumbly while moist, had turned into a mass of rock-hard clods when dry.

One very important aspect of good soil is something called 'humus'.

"Humus is vegetable or animal matter that has died and been changed by the action of soil organisms into a complex organic substance that becomes part of the soil".

There is an entire page in my book dedicated to humus. It is what gives rich soil it's texture, nutrients and water-holding capacity. It acts as a sponge, stops erosion, feeds beneficial organisms as well as earthworms, and contains all of the elements that plants need - and releases them slowly.

"Humus is the firm basis of good gardening. It is possible to grow inferior crops on humus-deficient soil by supplying all of your plants' chemical requirements, mainly in the form of nitrates, out of a fertilizer bag, but if you do this, your soil will progressively deteriorate and, ultimately blow or wash away, as the topsoils of so much of the world's surfact, abused by humankind, already have." ( p. 16 The new self-sufficient gardener)

My soil at the start, had practically NO humus.

The simplest way I can explain how to build in humus, is to relate it to nature. Think of the last time you walked into the forest. The ground there is spongy, as the layers of leaves, needles and decaying wood have built up. Over time, the sun and rain - along with fungi, bacteria and other decomposers have begun to turn all of this organic matter into dark, rich soil. But the soil cannot be easily seen! You would have to dig down, peel back the loose layers of this slowly decomposing matter to find the dark, rich, sweet-smelling soil underneath. The soil is protected by a thick covering which keeps it safe from erosion and deterioration.

Over the past three years as I've immersed myself into homesteading, organic gardening and permaculture principles - I've heard this re-iterated again and again. I've experimented with soil testing - but I have so many different areas and raised boxes - that it was tricky. Thankfully - I've learned that adding compost regularly will eliminate your need to balance the soil. The slow-releasing of complete nutrients in humus-rich soil is nature's way of fixing most problems. If my plants are suffering from something specific (like blossom end-rot for example - I know the soil there needs more calcium, and I can add this).

Ruth Stout (in the video linked below) talks about the incredible results she's had by keeping a very large layer of straw mulch on top of her garden. She never tills, and amazingly... rarely waters!

The 'Back to Eden' film (which can be viewed on vimeo) is another family who discovered amazing results (without tilling) by using large amounts of wood chips as a mulch layer.

This film has incredibly fascinating facts in it about soil, why it's important to preserve (rather than ignore it) and the problems that our modern farming systems have created. I highly recommend watching this. (You can watch instantly on Netflix).

Now... contrast what I described on the forest floor - with what we see in modern farming. It's no wonder we are confused when we want to start growing vegetables. If you drive by a typical farm - you'll see acres and acres of tilled soil - exposed to the elements - waiting for a new tilling or planting. Wait a few months, and usually you'll see corn or soy growing for miles. As the above quote says - you CAN grow vegetables this way. To grow plants, you really only need air, water and nutrients. Some farmers supply their plant's nutrients with chemical fertilizers, spreading manure and tilling- or both. On a very large scale, this seems to be the only way to produce in the quantities they are desiring.

BUT...

If you want to build your soil naturally.... the easiest way to do this, is to mimic what nature does, so well.

Back to our story. We had some really dense clay soil that first year. Because we didn't know any different but to till the soil, we bought a load of compost and mixed it in. That was a good first step, but we left the soil uncovered.

I am learning more with each passing year - through trial and error. But I've decided that if "humus is the firm basis of good gardening",then creating more humus-rich soil in my garden must be the goal.

Here are the steps that I am taking to do this.

- Compost everything that I can. Every bit of organic matter that I can find, goes into our compost heap. Kitchen scraps, lawn clippings, garden waste, dry leaves. In our setup, the compost pile is in the chicken yard. The hens eat what they want, scratch through it and it breaks down. We add pine shavings and/or straw to the chicken coop to keep the smell down, then - every week we rake it out and add this manure/bedding mixture to the compost heap. The combination of nitrogen-rich poop plus carbon-rich dry bedding - heats up well and breaks down beautifully. Usually in late summer or fall, I dig down and begin shoveling what is at the very bottom of the pile (it will be dark and crumbly) and put it into another pile (covered) to let mature. In the spring - this rich, dark and crumbly garden gold is ready to add to my garden. An important tip, when you think your compost is done... smell it! It should not have any bad odor like manure or ammonia, but should smell sweet. Here is a very helpful video to give you some more specifics on how to compost:

- Always keep the soil covered. I have been experimenting with mulching ever since I heard of Ruth Stout's methods. The benefits are - you keep your soil protected (like the forest floor) which is the ideal place for earthworms and beneficial bacteria and fungi to thrive. As that top mulch layer breaks down, it feeds the organisms in the soil - which give nutrients and texture (humus). It also holds in moisture, meaning you'll have to water less. I've tried using straw, leaves and wood chips on my garden. Really - you can use anything that will eventually break down - but it's good to know what works best for your climate. Living in Colorado - we have lots of sun in the summer, frozen winters and not as much rain. I've learned that things break down quickest when they have lots of heat and moisture. All winter here, since things are frozen - not much happens. Then, in the mid-summer - there's not much rain. I tried installing a drip system, wanting to conserve water - but that did not work well to help the mulch layers break down, as there was not enough moisture on the mulch to make this happen. Instead, my mulch layer on top remained dry and wanted to blow away - and the clay soil underneath created deep cracks where the water gravitated toward. I now have replaced the drippers with sprayer/misters to my system which moistens the entire top layer of the garden beds - allowing the mulch to get wet and decompose as well. I try to make sure and water in the evenings or early morning. I realize I will use more water this way, but I feel it's worth it, to benefit my soil.

- Look for compost/humus wherever possible, and add it generously with each new planting. This year, we expanded our garden from 1,673 square feet of space - to 2,359 square feet. We dug up the end of the driveway that we don't need, and got rid of more front lawn. Because of these large areas that we added - we needed large amounts of additional compost. More than our chicken yard and rabbits could provide. I also have some neighbors who are willing to let me farm their yards - which will require extra soil amending.

We have a favorite lake nearby, which we love to visit. The girls play and explore, and enjoy collecting driftwood. While there with a friend, I bent down and noticed how black and beautiful some soil was that had collected at one part of the shore. 'Look at all of this beautiful compost!!" (funny, the things I notice these days!)

I noticed that there was a place not too far where I could park, and determined to come back. I have since been back three times to collect loads of this beautiful humus-rich soil. I spread out a tarp in the back of my vehicle, brought along some large bushel baskets and would collect trash as I dug through the decomposing sticks to reveal layers and layers of rich compost (which hopefully included some fish that went belly-up as well). The area didn't have anything growing in it - so I felt good about taking some home.

Then, the other day as we were doing a dreaded chore (moving rock out from around our rasied beds) the girls and I noticed how much good compost there was in between the rocks. (This was due to leaves that break down over time). When I had a bit more time, I decided to see how much could be collected.

I grabbed a bit of leftover wire from an old rabbit hutch, set it on top of a 5 gallon bucket, and would shovel a pile of rocks on top, shake to sift, and dump the rocks away. This way, my rock pile was cleaner (just rocks, no soil mixed in) and I was able to collect about 5 buckets-full of lovely compost to add to some of my new beds! It was definitely a bit tedious - but I was thrilled to be outside working in the sun, and it felt great to end up with a nice (free) little load of humus.

For the rest of my compost needs, I have been asking around to friends - hoping to find a farm with more animals who might have some aged manure. Yesterday, we found just the person! A neighbor of our family has a HUGE pile of cow manure that has been aging (and has been turned a few times). He has enough that he was willing to share with me before he spread it out on his fields. We looked for the part of the pile that was oldest, and dug to the bottom. It was dark, crumbly and lovely - and smelled sweet. Perfect!! I will be getting my exercise shoveling and filling up the trailer several times this week to gather enough.

If you are looking to add compost to your garden, but don't have animals - it makes sense to ask around. You could certainly buy it at a garden center, but there are plenty of people who will sell - or give it to you for free. Compost, rich in humus - I believe, is the absolute key to a bountiful garden.

Here are a few pictures of my garden beds this year. In the fall I spread out some rabbit manure on each bed, and covered them with as many fall leaves as I could. Some beds got another layer of straw as well. As this is only my second year experimenting with deep mulching, I still have quite a bit of clay in the soil below. I don't mix in the leaves, because mixing in too much carbon-rich content (dry leaves, wood chips that haven't decomposed) will tie up the nitrogen in the soil - and make it unavailable to the plants. Just using them as a top layer will protect the soil and draw up the earthworms and decomposers - and they will do the job of enriching the soil. I also don't till anymore - because I've read that too much disturbance in the soil can hinder the microbial growth in the soil.

I have been going around with a large fork to lift the clay soil beneath - aerating the beds a bit, and breaking it up a bit. This will allow the microbes to get in, and when I add more compost when I plant, will give some air to the ground below.

When I am direct-seeding plants like carrots, onions, beets or peas - I spread away the mulch layer, add a nice layer of compost to plant in and let them germinate. I've noticed that I didn't have good luck with my seeds germinating when I tried to sow the seeds and then cover deeply again with mulch. There was not enough warmth in early Spring for mine to germinate well. After they emerge from the soil and get a few inches tall, though I will move the mulch layer back around the plants to protect it.

I have had very good luck with my raised boxes on the south side of my garden. I believe it's because of a few things. I get lots of hot sun on this side, and they thaw out earlier than the ground thaws - being raised up. I have been watering evenly with the sprayers, and the sides of the boxes keep the mulch in place (it doesn't blow away as easily).

I used a guide from the Square Foot Gardening method to build the soil when I first filled the boxes.

'Mel's Mix' is:

1/3 peat moss,

1/3 vermiculite,

1/3 compost (from as many sources as possible).

I've added rabbit poop and compost to the tops of the beds after the plants are done in the fall, then covered with thick layers of mulch (straw, leaves) before winter.

In the spring - this is what I find. TONS of earthworms and dark, crumbly rich soil! Excited to plant again in these boxes!

I hope this information is helpful to those of you who are on this adventure of growing food.

Remember... in order to get this:

You've got to first start building this:

Happy gardening!